“There’s No Place Like Home”

By Tom Nugent

Forty-three years after being raised in a Catholic orphanage near Chicago, Sal Di Leo (BS ’77) went back to say thanks to the nuns who’d saved his life, once upon a time.

A successful business consultant today, the 57-year-old Di Leo found several of the Sisters of St. Francis living in retirement in Joliet, Illinois. Blinking back tears, he told them how grateful he was for their help during his struggling, poverty-wracked childhood. Then he wrapped his arms around a white-haired nun, Sister David Ann Hoy, now aged 82.

The two of them enjoyed a long, satisfying hug.

“Is this incredible, or what?” said the former UNL education major, as he hurried from one nun to the next in order to offer them his fervent thanks.

It was an unforgettable moment, to say the least. But Sal Di Leo’s touching story – Orphan Boy Makes Good! – also contains a fascinating twist.

In a dark and unexpected chapter that might have been written in Hollywood, the Di Leo Saga includes a dramatic “fall from grace” . . . a searing mid-life crisis in which the wealthy entrepreneur went bankrupt, became addicted to drugs and alcohol, and then came very close to taking his own life with a shotgun.

During that life-or-death crisis 25 years ago, the Sisters of St. Francis once again stepped forward to help save Sal from destruction.

By Tom Nugent

—Joliet, Illinois

On the worst day of Sal Di Leo’s amazing life, a smiling woman in a snow-white veil brought him a gift he would never forget.

It was a metal tray loaded with roast beef, gravy, green beans, potatoes and carrots. Along with the tray, the woman in white gave him a glass of milk and “a little dessert bowl full of canned peaches.”

Sal was eight years old on that winter afternoon nearly half a century ago. As he looked at the delectable goodies stacked high on the tray, his eyes grew huge. “It was the first time in my life,” he would later recall, “that I’d ever seen so much food sitting on a plate at one time.”

Unable to believe his good fortune, the little boy asked the smiling nun in a quavering voice: “Is all of this for me, sister?”

“It sure is,” said the nun, who was a member of the St. Francis Sisters of the Immaculate Heart. “You go right ahead and dig in!”

It happened on a cold, blustery afternoon in March of 1963 – about two hours after the terrified Di Leo was removed from his dysfunctional home in Joliet by social workers . . . and then transferred (along with three of his siblings) to the nearby Guardian Angel Home, operated by the locally based Sisters of St. Francis of Mary Immaculate.

For Di Leo, the author of a moving autobiography that tells the story of his rescue by the nuns in gripping detail (Did I Ever Thank You, Sister? – now available at www.amazon.com and www.barnesandnoble.com), the forced removal to the orphanage was the start of a nine-year odyssey that would finally end when he checked into UNL’s Harper Hall as a freshman in the fall of 1972.

Deserted by their mentally disturbed father and utterly penniless, Sal and his 11 siblings had been living through “a nightmare of neglect and poverty,” when the local authorities decided to intervene. Only a third grader at the time, the youthful Di Leo was deeply alarmed by the sudden removal to the “huge stone building” on the hill, where more than 150 orphans lived under the care of the nuns. As he would later write in his moving account of the experience:

That

“I could hear the banging of the old radiators as the sounds came up from the bowels of the building while everyone else silently slept. I wondered if it was true when Philip had said that there were bad kids banging on the pipes to let someone know they were there and they wanted to get out. I also could not get out of my head the . . . wish that I was not there and that things could be different.

I stared for a long time into the night at the glimmering moonlight on the ceiling and I found myself making a vow I would never forget. I said, “Oh, God, help me make sure that if I ever have kids someday, they never have to feel pain and be alone.” The tears rushed down my face and I finally fell asleep from exhaustion.

A Wealthy Man by Age 30 . . . And Then Bankrupt

Sal Di Leo would ultimately spend more than five years at the Guardian Angel Home, before going on to a four-year sojourn at Boys Town in Omaha and then a successful college career at UNL. The story of his gritty survival as a poverty-stricken orphan is deeply compelling, of course. And yet it seems almost tame, when compared to the astonishing saga of his later life. A brilliant entrepreneur in business, Di Leo became wealthy beyond his wildest dreams – by the age of 30.

But the hunger that drove him also contained the seeds of his financial destruction. As a self-described “moral failure” whose “highly unethical business practices” would eventually paralyze him with guilt, Di Leo became a money-obsessed, hard-drinking business exec whose excesses finally left him afraid to look at himself in the mirror each day.

“The reality is that I lost my moral compass after leaving UNL,” Di Leo says today. “After spending all those years as an orphan, I became consumed by the desire to make money. I thought that if I could just pile up enough dollars, I’d finally begin to feel good about myself. But I was wrong, dead wrong.

“I was financially secure by the age of 30,” he recalls, “and I was completely miserable.”

Di Leo’s financial success was undeniable, however. After launching a national chain of appliance-rental outlets (based in Baton Rouge, La.) in the early 1980s, he’d quickly built his fledgling enterprise into a profit-making machine. With dozens of branches, his high-flying leasing outfit was quickly selling franchises – most of which were racking up huge sales. But the more money Sal made, the worse he seemed to feel.

“I was doing very well financially,” he recalls today, “but I knew I was making money by charging exorbitant rates to people who couldn’t afford to rent our TV sets and stereos and other electronic gear. And as soon as they missed a payment, we’d move in and repossess the appliances and then rent them to the next poor souls who didn’t realize what they were getting into.

“It was wrong, and deep down, I knew it was wrong. I started drinking heavily and started taking drugs.”

In the end, the confused and increasingly conflicted entrepreneur ran his million-dollar-a-year gold mine straight into the ground, by drinking too much and taking too many “reckless financial risks.” By late 1985, most of his outlets were shuttered and he was broke. And he was utterly desperate.

On a “truly terrible afternoon” in December of 1985, Di Leo went out to his garage in Baton Rouge and took a long hard look at the Remington 16 gauge shotgun hanging on the wall. Then he unhooked it and carried it into the house. He inserted a shell into the barrel. Then he sat down, holding the gun in his lap. His wife and their two young daughters were off on a shopping trip . . . and all he needed now was the courage to pull that trigger. “At that terrible point in my life,” Di Leo recalls, “I really felt like I was worth more dead than alive . . . and I felt compelled to pull the trigger in order to save my family, so that they would at least have some insurance money.”

But then came a sudden impulse. “For some reason, I hesitated,” Di Leo remembers, “and all at once, Sister Paul [one of the nuns who had raised him at the orphanage] jumped into my head. I felt total despair, and I needed a last prayer before I took my life. So I called the Mother House for the Sisters of St. Francis.”

It would be his way of saying goodbye to everything.

Di Leo dialed the number. He held his breath. He hadn’t spoken with Sister Paul – the nun he’d been closest to as a boy – in more than 18 years. And then, all at once, she was on the line and greeting him cheerfully. Here’s how Sal described the moment in his 1999 autobiography:

Finally, I heard her voice on the other line, “Hello. This is Sister Paul. Who’s calling?” she asked. Her voice sounded just like it used to. She was sure and steady. It was good to hear her voice. I didn’t quite know what to say, though.

“Sister Paul,” I said, “this is Sal Di Leo. Do you remember me?” I asked.

“Sal Di Leo. How would I forget you and how are you?” she asked in her kind and reassuring voice. I felt alive again.

Sister Paul and I talked for almost half an hour. She asked me about my brother and my sisters. I told her my older sister had become a nun, too, and my little sister was living in Alaska and apparently doing well. When she asked about me, I told her I was fine and doing OK. I didn’t tell her how bad things were for me. But I think she knew somehow that things weren’t as I pretended. She asked: “Are you still going to church?”

“No, Sister. I left the Church,” I said.

“Then get back. Find a priest, go to confession, and receive Communion. You know you can’t go through life without God,” she finished.

I knew she was right. Tears were running down my face as I said I would and hung up. I went to the garage and hung the gun back up on the wall. When my wife and the kids came home, I hugged them a little tighter.

That phone call to the Guardian Angel Home marked a decisive turning-point in Sal Di Leo’s roller-coaster life. Renewed and reenergized, he borrowed $7,000 from his in-laws and moved his young family to Minneapolis, where he soon went back to work – not as a high-rolling, risk-taking entrepreneur, but as an ordinary nine-to-five manager of a local furniture store.

Although several years of difficult struggle still lay ahead, Di Leo’s life was now back on track. He would never be wealthy again, and that was fine with him. “It took me a dozen years – and a great deal of mental suffering – to understand that mere money couldn’t make me happy,” he says today. “I spent several years in counseling, and I thank God that my wonderful wife never gave up on me.

“Eventually, I came to understand that my obsessive-compulsive lifestyle had been a compensation mechanism – a futile psychological strategy in which I was trying to overcome my dread of being dependent on other people by making tons and tons of money. Those early years of struggle had taken their toll on me . . . had left me desperate to prove I could take care of myself, instead of relying on others to feed and clothe me.

“Once I understood the compulsions that were driving me, I could begin to overcome them. But it wouldn’t have happened without the help of so many other people . . . and when I look back on the assistance I got from my loving wife and the wonderful nuns and the counselors, I’m just eternally grateful.

“Really, I’m the luckiest guy I’ve ever met!”

Enjoying “The Thrill of Freedom” at UNL

When Sal Di Leo arrived on the campus of UNL – fresh from a four-year residency at the famed Boys Town orphanage in Omaha – he was “amazed and delighted by the sudden freedom” he was allowed to enjoy.

“For nearly ten years, I’d been living the highly regimented life of an orphan in an institution,” he recalled during a recent interview in Joliet. “Now, all at once, I was just another freshman living in a college dorm.

“At first I could hardly believe it. Just walking around the campus by myself was a thrill. Just enjoying the warm summer air, as I walked past the big fountain near the Student Union – that was a big adventure for me. And when I realized that I could go get a cup of coffee or a slice of pizza anytime I wanted, I could hardly believe my good luck.”

Di Leo says his exhilarating sense of freedom only increased during his first-ever class at UNL, where he came face to face with an English Lit instructor whose freewheeling teaching style really turned him on to short stories and novels. “My first class really set the pace for me,” he would write later in his autobiography. “It was a literature professor named Clyde Burkholder. I walked in that first day and he was sitting on top of his desk, just talking to a couple of kids. He gave us our syllabus and told us we didn’t have to show up for class if we didn’t want to, and it was up to us if we wanted to learn. I was used to the regimented Boys Town classes.

“I thought he was such a cool guy. I really enjoyed his class.”

As the months passed, the gung-ho freshman savored one adventure after the next. Soon he was working part-time in a campus microbiology lab, and dating a girl who lived in a nearby dorm . . . and also shouting his lungs out at Cornhusker football games. “The 1970s were great years for Nebraska football,” he remembers with a smile of nostalgia, “and many of us who were part of the old ‘Knothole Gang’ still remember the excitement of watching great athletes like Dave Humm throw long touchdown passes on those wonderful Saturday afternoons at the stadium.”

After receiving his B.S. in Education in the spring of ’77, Di Leo signed on as a fourth-grade teacher at a public school in Fremont, Nebraska, where he earned a thoroughly unimpressive $7,000 per annum. But his heart wasn’t really in teaching, and within a year he’d handed in his resignation. Deep down, he was burning with a desire to make money – lots and lots of money. To do that, he understood that “working for a wage” wasn’t enough; if he wanted to become truly wealthy, he would have to become a successful entrepreneur. After a couple of years as a hard-charging salesman at an appliance-rental company, he was convinced he knew enough to build his own franchise operation . . . and managed to convince several banks to loan him $300,000 in order to launch his first two stores in Baton Rouge and Jackson, Mississippi.

And so it began – Sal Di Leo’s long, arduous journey from astonishing business success and fabulous wealth to Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Ask him to describe the collapse of his business empire in the mid-1980s and he’ll tell you: “That bankruptcy was the best thing that ever happened to me – that and my decision to call Sister Paul, instead of killing myselfwith my shotgun.”

For Di Leo, who has returned to the Joliet orphanage several times over the years in order to thank the nuns for their work, the “great blessing” of his life has been the “gift of understanding” that what matters most is the “willingness to give of yourself” to the community in which you live.

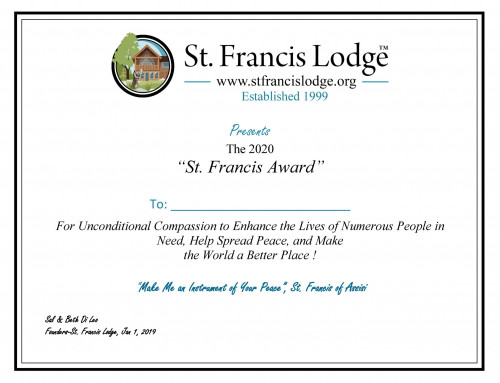

Only a year and a half ago, Di Leo was able to do precisely that. After putting up $320,000 of his own money and with the help of some other “wonderful volunteers,” he and his wife (they recently celebrated their 30th anniversary) participated in the “official dedication and blessing” of the St. Francis Lodge – a free vacation and spiritual retreat center for nuns (and especially St. Francis nuns) in rural Minnesota.

Located in a bucolic and vernal setting at Lake George (near Bemidji), the St. Francis Lodge is the ideal resting place for religious clerics of all faiths who need time to relax and meditate, according to Di Leo. “I can’t tell you how much it means to me,” he said the other day, “to know that the good nuns who took care of me early in life are now able to rest and relax at the Lodge, and especially during the spring and summer, when the lake and its environs seem especially beautiful.”

Then he paused for a moment to reflect on his thoroughly remarkable life – and on the two “miracles” that came when he needed them most. “I’m indebted,” he said, “to so many good people who’ve helped me along the way. They are the heroes in my life.

“I just hope I can send the message from my life that it is so important to stop and recognize the good in our lives, and to thank those who help us. That’s a big part of what success really is. Gratitude leads to ‘passing it on,’ and it’s very freeing!”

***

During his recent visit to the St. Francis Retirement Home in Joliet, Di Leo glowed with joyful energy as he invited one elderly nun after the next to visit the lakeside retreat center.

The nuns responded in kind. Sister David Hoy, who’d been one of Di Leo’s favorites during his stay at the Guardian Home 45 years before, told a rollicking story of how the nine-year-old Di Leo had once tried to dispose of a lunchtime orange he didn’t want to eat.

“We were riding on a school bus that day,” said the white-haired, 82-year-old nun, “and when we got off the bus for lunch, Sal took a look around to make sure nobody was watching him. Then he knelt down and stuck the orange under one of the bus tires, so that that it would be squashed flat when we drove away.

“Well, I spotted him. So I shouted to the bus driver: ‘Don’t move!’ I retrieved the orange and I told him: ‘Sal, it’s okay if you don’t want to eat the orange – but we shouldn’t waste it. Let’s take it back home and see if somebody else wants it, what do you say?’”

Laughter all around.

And then a few minutes later, it was time to go. Sal Di Leo’s visit to his old friends was ending. It was time for Sal to return to his life in Minneapolis, where he’s been working as a successful business consultant for the past decade or so. And so he went from one Sister of St. Francis to the next, while hugging and smiling and vowing that he would see them all again soon.

“Sal was all boy,” laughed Sister David Ann, moments after surviving a rib-crunching bear-hug from her once-upon-a-time charge. “He was a handful at times, let me tell you. But he was also a kind-hearted little fellow with lots of goodness in him.

“It’s wonderful to see what a fine man he’s become!”

#####

There’s No Place Like Home

Forty-three years after being raised in a Catholic orphanage near Chicago, Sal Di Leo (BS ’77) went back to say thanks to the nuns who’d saved his life, once upon a time.

A successful business consultant today, the 57-year-old Di Leo found several of the Sisters of St. Francis living in retirement in Joliet, Illinois. Blinking back tears, he told them how grateful he was for their help during his struggling, poverty-wracked childhood. Then he wrapped his arms around a white-haired nun, Sister David Ann Hoy, now aged 82.

The two of them enjoyed a long, satisfying hug.

“Is this incredible, or what?” said the former UNL education major, as he hurried from one nun to the next in order to offer them his fervent thanks.

It was an unforgettable moment, to say the least. But Sal Di Leo’s touching story – Orphan Boy Makes Good! – also contains a fascinating twist.

In a dark and unexpected chapter that might have been written in Hollywood, the Di Leo Saga includes a dramatic “fall from grace” . . . a searing mid-life crisis in which the wealthy entrepreneur went bankrupt, became addicted to drugs and alcohol, and then came very close to taking his own life with a shotgun.

During that life-or-death crisis 25 years ago, the Sisters of St. Francis once again stepped forward to help save Sal from destruction.

By Tom Nugent

—Joliet, Illinois

On the worst day of Sal Di Leo’s amazing life, a smiling woman in a snow-white veil brought him a gift he would never forget.

It was a metal tray loaded with roast beef, gravy, green beans, potatoes and carrots. Along with the tray, the woman in white gave him a glass of milk and “a little dessert bowl full of canned peaches.”

Sal was eight years old on that winter afternoon nearly half a century ago. As he looked at the delectable goodies stacked high on the tray, his eyes grew huge. “It was the first time in my life,” he would later recall, “that I’d ever seen so much food sitting on a plate at one time.”

Unable to believe his good fortune, the little boy asked the smiling nun in a quavering voice: “Is all of this for me, sister?”

“It sure is,” said the nun, who was a member of the St. Francis Sisters of the Immaculate Heart. “You go right ahead and dig in!”

It happened on a cold, blustery afternoon in March of 1963 – about two hours after the terrified Di Leo was removed from his dysfunctional home in Joliet by social workers . . . and then transferred (along with three of his siblings) to the nearby Guardian Angel Home, operated by the locally based Sisters of St. Francis of Mary Immaculate.

For Di Leo, the author of a moving autobiography that tells the story of his rescue by the nuns in gripping detail (Did I Ever Thank You, Sister? – now available at www.amazon.com and www.barnesandnoble.com), the forced removal to the orphanage was the start of a nine-year odyssey that would finally end when he checked into UNL’s Harper Hall as a freshman in the fall of 1972.

Deserted by their mentally disturbed father and utterly penniless, Sal and his 11 siblings had been living through “a nightmare of neglect and poverty,” when the local authorities decided to intervene. Only a third grader at the time, the youthful Di Leo was deeply alarmed by the sudden removal to the “huge stone building” on the hill, where more than 150 orphans lived under the care of the nuns. As he would later write in his moving account of the experience:

That [first] night, as I lay in the dark dormitory room with all the other little boys, lined up in our beds in rows and rows, I looked up at the ceiling late into the night. I found myself watching a soft light on the ceiling that crept in from the moon outside and was shining in our room. The winds of March whistled outside our window and sounded angry as they whipped up against the old stone structure with a vengeance.

“I could hear the banging of the old radiators as the sounds came up from the bowels of the building while everyone else silently slept. I wondered if it was true when Philip had said that there were bad kids banging on the pipes to let someone know they were there and they wanted to get out. I also could not get out of my head the . . . wish that I was not there and that things could be different.

I stared for a long time into the night at the glimmering moonlight on the ceiling and I found myself making a vow I would never forget. I said, “Oh, God, help me make sure that if I ever have kids someday, they never have to feel pain and be alone.” The tears rushed down my face and I finally fell asleep from exhaustion.

A Wealthy Man by Age 30 . . . And Then Bankrupt

Sal Di Leo would ultimately spend more than five years at the Guardian Angel Home, before going on to a four-year sojourn at Boys Town in Omaha and then a successful college career at UNL. The story of his gritty survival as a poverty-stricken orphan is deeply compelling, of course. And yet it seems almost tame, when compared to the astonishing saga of his later life. A brilliant entrepreneur in business, Di Leo became wealthy beyond his wildest dreams – by the age of 30.

But the hunger that drove him also contained the seeds of his financial destruction. As a self-described “moral failure” whose “highly unethical business practices” would eventually paralyze him with guilt, Di Leo became a money-obsessed, hard-drinking business exec whose excesses finally left him afraid to look at himself in the mirror each day.

“The reality is that I lost my moral compass after leaving UNL,” Di Leo says today. “After spending all those years as an orphan, I became consumed by the desire to make money. I thought that if I could just pile up enough dollars, I’d finally begin to feel good about myself. But I was wrong, dead wrong.

“I was financially secure by the age of 30,” he recalls, “and I was completely miserable.”

Di Leo’s financial success was undeniable, however. After launching a national chain of appliance-rental outlets (based in Baton Rouge, La.) in the early 1980s, he’d quickly built his fledgling enterprise into a profit-making machine. With dozens of branches, his high-flying leasing outfit was quickly selling franchises – most of which were racking up huge sales. But the more money Sal made, the worse he seemed to feel.

“I was doing very well financially,” he recalls today, “but I knew I was making money by charging exorbitant rates to people who couldn’t afford to rent our TV sets and stereos and other electronic gear. And as soon as they missed a payment, we’d move in and repossess the appliances and then rent them to the next poor souls who didn’t realize what they were getting into.

“It was wrong, and deep down, I knew it was wrong. I started drinking heavily and started taking drugs.”

In the end, the confused and increasingly conflicted entrepreneur ran his million-dollar-a-year gold mine straight into the ground, by drinking too much and taking too many “reckless financial risks.” By late 1985, most of his outlets were shuttered and he was broke. And he was utterly desperate.

On a “truly terrible afternoon” in December of 1985, Di Leo went out to his garage in Baton Rouge and took a long hard look at the Remington 16 gauge shotgun hanging on the wall. Then he unhooked it and carried it into the house. He inserted a shell into the barrel. Then he sat down, holding the gun in his lap. His wife and their two young daughters were off on a shopping trip . . . and all he needed now was the courage to pull that trigger. “At that terrible point in my life,” Di Leo recalls, “I really felt like I was worth more dead than alive . . . and I felt compelled to pull the trigger in order to save my family, so that they would at least have some insurance money.”

But then came a sudden impulse. “For some reason, I hesitated,” Di Leo remembers, “and all at once, Sister Paul [one of the nuns who had raised him at the orphanage] jumped into my head. I felt total despair, and I needed a last prayer before I took my life. So I called the Mother House for the Sisters of St. Francis.”

It would be his way of saying goodbye to everything.

Di Leo dialed the number. He held his breath. He hadn’t spoken with Sister Paul – the nun he’d been closest to as a boy – in more than 18 years. And then, all at once, she was on the line and greeting him cheerfully. Here’s how Sal described the moment in his 1999 autobiography:

Finally, I heard her voice on the other line, “Hello. This is Sister Paul. Who’s calling?” she asked. Her voice sounded just like it used to. She was sure and steady. It was good to hear her voice. I didn’t quite know what to say, though.

“Sister Paul,” I said, “this is Sal Di Leo. Do you remember me?” I asked.

“Sal Di Leo. How would I forget you and how are you?” she asked in her kind and reassuring voice. I felt alive again.

Sister Paul and I talked for almost half an hour. She asked me about my brother and my sisters. I told her my older sister had become a nun, too, and my little sister was living in Alaska and apparently doing well. When she asked about me, I told her I was fine and doing OK. I didn’t tell her how bad things were for me. But I think she knew somehow that things weren’t as I pretended. She asked: “Are you still going to church?”

“No, Sister. I left the Church,” I said.

“Then get back. Find a priest, go to confession, and receive Communion. You know you can’t go through life without God,” she finished.

I knew she was right. Tears were running down my face as I said I would and hung up. I went to the garage and hung the gun back up on the wall. When my wife and the kids came home, I hugged them a little tighter.

That phone call to the Guardian Angel Home marked a decisive turning-point in Sal Di Leo’s roller-coaster life. Renewed and reenergized, he borrowed $7,000 from his in-laws and moved his young family to Minneapolis, where he soon went back to work – not as a high-rolling, risk-taking entrepreneur, but as an ordinary nine-to-five manager of a local furniture store.

Although several years of difficult struggle still lay ahead, Di Leo’s life was now back on track. He would never be wealthy again, and that was fine with him. “It took me a dozen years – and a great deal of mental suffering – to understand that mere money couldn’t make me happy,” he says today. “I spent several years in counseling, and I thank God that my wonderful wife never gave up on me.

“Eventually, I came to understand that my obsessive-compulsive lifestyle had been a compensation mechanism – a futile psychological strategy in which I was trying to overcome my dread of being dependent on other people by making tons and tons of money. Those early years of struggle had taken their toll on me . . . had left me desperate to prove I could take care of myself, instead of relying on others to feed and clothe me.

“Once I understood the compulsions that were driving me, I could begin to overcome them. But it wouldn’t have happened without the help of so many other people . . . and when I look back on the assistance I got from my loving wife and the wonderful nuns and the counselors, I’m just eternally grateful.

“Really, I’m the luckiest guy I’ve ever met!”

Enjoying “The Thrill of Freedom” at UNL

When Sal Di Leo arrived on the campus of UNL – fresh from a four-year residency at the famed Boys Town orphanage in Omaha – he was “amazed and delighted by the sudden freedom” he was allowed to enjoy.

“For nearly ten years, I’d been living the highly regimented life of an orphan in an institution,” he recalled during a recent interview in Joliet. “Now, all at once, I was just another freshman living in a college dorm.

“At first I could hardly believe it. Just walking around the campus by myself was a thrill. Just enjoying the warm summer air, as I walked past the big fountain near the Student Union – that was a big adventure for me. And when I realized that I could go get a cup of coffee or a slice of pizza anytime I wanted, I could hardly believe my good luck.”

Di Leo says his exhilarating sense of freedom only increased during his first-ever class at UNL, where he came face to face with an English Lit instructor whose freewheeling teaching style really turned him on to short stories and novels. “My first class really set the pace for me,” he would write later in his autobiography. “It was a literature professor named Clyde Burkholder. I walked in that first day and he was sitting on top of his desk, just talking to a couple of kids. He gave us our syllabus and told us we didn’t have to show up for class if we didn’t want to, and it was up to us if we wanted to learn. I was used to the regimented Boys Town classes.

“I thought he was such a cool guy. I really enjoyed his class.”

As the months passed, the gung-ho freshman savored one adventure after the next. Soon he was working part-time in a campus microbiology lab, and dating a girl who lived in a nearby dorm . . . and also shouting his lungs out at Cornhusker football games. “The 1970s were great years for Nebraska football,” he remembers with a smile of nostalgia, “and many of us who were part of the old ‘Knothole Gang’ still remember the excitement of watching great athletes like Dave Humm throw long touchdown passes on those wonderful Saturday afternoons at the stadium.”

After receiving his B.S. in Education in the spring of ’77, Di Leo signed on as a fourth-grade teacher at a public school in Fremont, Nebraska, where he earned a thoroughly unimpressive $7,000 per annum. But his heart wasn’t really in teaching, and within a year he’d handed in his resignation. Deep down, he was burning with a desire to make money – lots and lots of money. To do that, he understood that “working for a wage” wasn’t enough; if he wanted to become truly wealthy, he would have to become a successful entrepreneur. After a couple of years as a hard-charging salesman at an appliance-rental company, he was convinced he knew enough to build his own franchise operation . . . and managed to convince several banks to loan him $300,000 in order to launch his first two stores in Baton Rouge and Jackson, Mississippi.

And so it began – Sal Di Leo’s long, arduous journey from astonishing business success and fabulous wealth to Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Ask him to describe the collapse of his business empire in the mid-1980s and he’ll tell you: “That bankruptcy was the best thing that ever happened to me – that and my decision to call Sister Paul, instead of killing myselfwith my shotgun.”

For Di Leo, who has returned to the Joliet orphanage several times over the years in order to thank the nuns for their work, the “great blessing” of his life has been the “gift of understanding” that what matters most is the “willingness to give of yourself” to the community in which you live.

Only a year and a half ago, Di Leo was able to do precisely that. After putting up $320,000 of his own money and with the help of some other “wonderful volunteers,” he and his wife (they recently celebrated their 30th anniversary) participated in the “official dedication and blessing” of the St. Francis Lodge – a free vacation and spiritual retreat center for nuns (and especially St. Francis nuns) in rural Minnesota.

Located in a bucolic and vernal setting at Lake George (near Bemidji), the St. Francis Lodge is the ideal resting place for religious clerics of all faiths who need time to relax and meditate, according to Di Leo. “I can’t tell you how much it means to me,” he said the other day, “to know that the good nuns who took care of me early in life are now able to rest and relax at the Lodge, and especially during the spring and summer, when the lake and its environs seem especially beautiful.”

Then he paused for a moment to reflect on his thoroughly remarkable life – and on the two “miracles” that came when he needed them most. “I’m indebted,” he said, “to so many good people who’ve helped me along the way. They are the heroes in my life.

“I just hope I can send the message from my life that it is so important to stop and recognize the good in our lives, and to thank those who help us. That’s a big part of what success really is. Gratitude leads to ‘passing it on,’ and it’s very freeing!”

***

During his recent visit to the St. Francis Retirement Home in Joliet, Di Leo glowed with joyful energy as he invited one elderly nun after the next to visit the lakeside retreat center.

The nuns responded in kind. Sister David Hoy, who’d been one of Di Leo’s favorites during his stay at the Guardian Home 45 years before, told a rollicking story of how the nine-year-old Di Leo had once tried to dispose of a lunchtime orange he didn’t want to eat.

“We were riding on a school bus that day,” said the white-haired, 82-year-old nun, “and when we got off the bus for lunch, Sal took a look around to make sure nobody was watching him. Then he knelt down and stuck the orange under one of the bus tires, so that that it would be squashed flat when we drove away.

“Well, I spotted him. So I shouted to the bus driver: ‘Don’t move!’ I retrieved the orange and I told him: ‘Sal, it’s okay if you don’t want to eat the orange – but we shouldn’t waste it. Let’s take it back home and see if somebody else wants it, what do you say?’”

Laughter all around.

And then a few minutes later, it was time to go. Sal Di Leo’s visit to his old friends was ending. It was time for Sal to return to his life in Minneapolis, where he’s been working as a successful business consultant for the past decade or so. And so he went from one Sister of St. Francis to the next, while hugging and smiling and vowing that he would see them all again soon.

“Sal was all boy,” laughed Sister David Ann, moments after surviving a rib-crunching bear-hug from her once-upon-a-time charge. “He was a handful at times, let me tell you. But he was also a kind-hearted little fellow with lots of goodness in him.

“It’s wonderful to see what a fine man he’s become!”

#####

Leave A Comment